It took a monarch butterfly three years to find my milkweed patch. Since then, I get visitors every year. At first only adults traveling south in the fall stopped by to fuel up on fall blooming flowers and to lay single white eggs on the bottom surface of milkweed leaves. It took another couple of years before I started to get visitors in the spring, also stopping along their migration route to fuel and lay eggs. During spring, monarchs are moving north, following the wave of warmer weather, when milkweed starts to regrow after a dormant winter. Where are they coming from? Eastern monarchs overwinter in Mexican forests, nearly 2 miles above sea level. They migrate nearly 2500 miles between winter forests in Mexico and their breeding grounds of the eastern US and Canada. This spring (2022) my garden has been wonderfully abundant with monarchs.

My first sighting this year was an adult female on April 13. In 2019 I also recorded first sightings of butterfly visitors and that year I hadn’t spotted an adult monarch until July 26. The milkweed in April was newly sprouted. I suspected she was laying eggs but didn’t investigate until I was gardening later that week. I wanted to remove milkweed from an area I hadn’t wished it to grow, but discovered the eggs, luckily before tossing the plant into the compost heap. I raised up the caterpillars (cats) that (later in the week) emerged from the tiny eggs and followed the progress of their growth into pupation where they quietly concealed themselves inside their chrysalids of gold studded green.

Later in the month I got to watch a second female as she laid her eggs. She fluttered from one milkweed plant to another, stopped briefly, moved on. She was very focused and inconspicuous. It was a pleasure to watch.

I counted 19 cats one day in May this season, living on the milkweed in my pollinator garden. Other than the cats I raised up myself, I found no signs of pupation, but no doubt they were close by. I’ve seen them crawl a considerable distance to find a safe haven to rest while metamorphosis unravels, so it’s quite possible they were present although unseen.

One morning, the day after a thunder storm, I witnessed a caterpillar behavior I hadn’t seen before. While weeding my garden I discovered at least a half dozen cats on plants other than milkweed, cats that weren’t at that time ready to pupate. We were experiencing some unusually cold temperatures for that time of year in the piedmont of NC so I’m not sure if they were taking storm cover and then were yet too cold to move or if there was another reason for this discovery. Regardless, I weeded with care and returned my rogue cats onto leafy milkweed stalks. Some took up to 20 minutes to enliven and grip onto their host plant in order to resume eating the only vegetation they can eat as monarch larvae.

My other discovery that morning was seeing the bare stalks of milkweed with new leaf growth. The plants have the whole summer to recover their growth after offering their nutrition to the first generation of this year’s cats. The next round of feeding will be in the fall and between now and then, the plants will work to re-leaf and flower. It’s a wonder to see how pleasantly symbiotic the whole relationship is. The milkweed relinquishes its leaves while maintaining life sustaining energy in its deep taproot and regrows. The caterpillar receives its nourishment, including the bitter toxin from the plant that provides a layer of protection from predators, even as an adult. Pollinators will be by eventually to pollinate the flowers which will create pods of wind-dispersed seeds. Human interactions don’t ever seem this smoothly cooperative.

I do believe patience to be a virtue and watching monarchs and caterpillars operate so freely on the milkweed I planted for them years ago is the virtuous reward I was seeking.

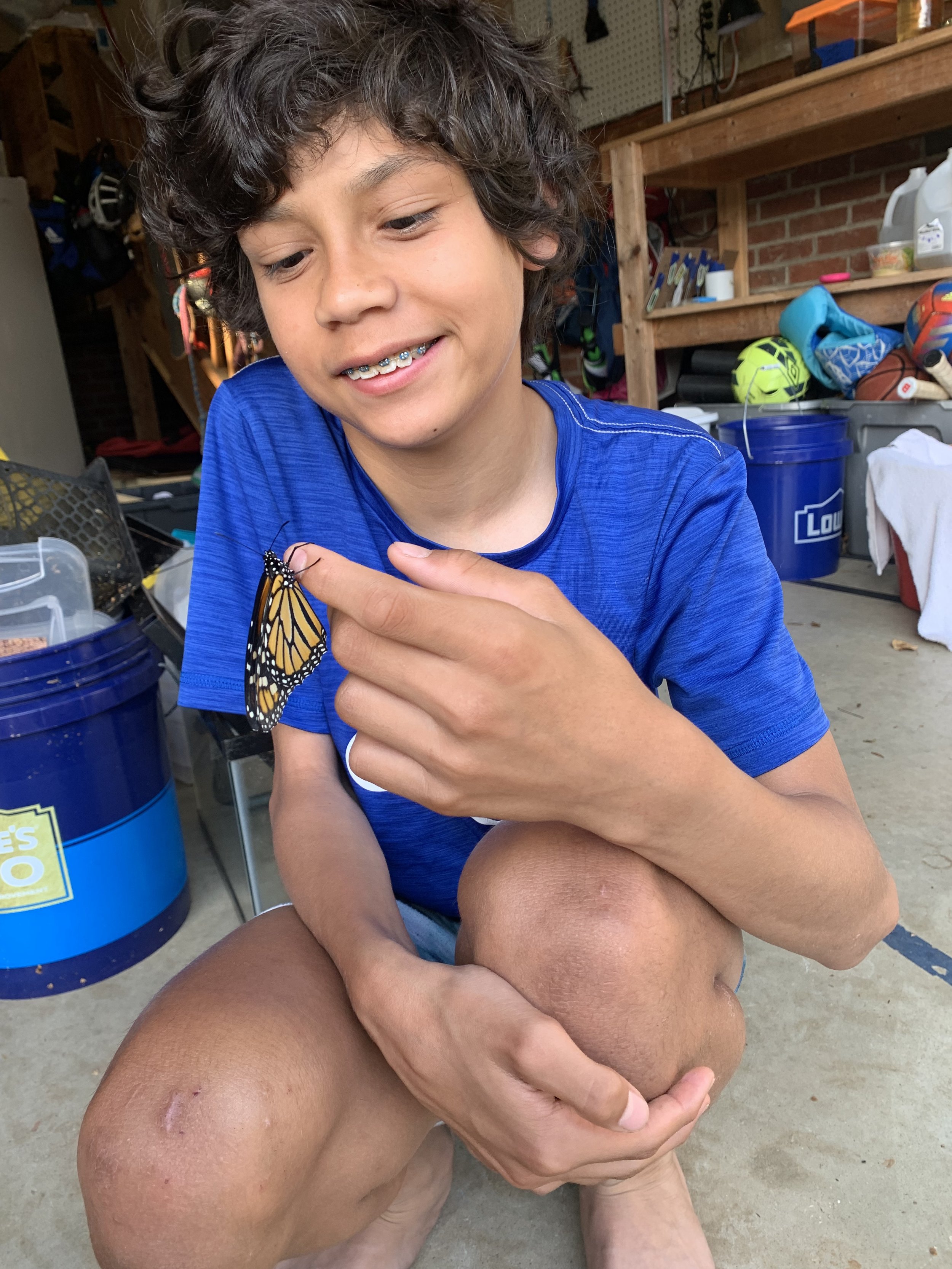

Photos of This Year’s Spring Migrants (2022)

Visit the Dragonfly Nature Programs Facebook page to view the photo album “Wildlife Encounters with Butterflies at Home” to see my record of every first time sighting of all butterfly species in my garden this summer.

Growing Milkweed

Growing seeds in a milkjug protects them from being eaten.

The “milk” in the plant’s name refers to the bitter, sticky, white fluid that drips from the plant when you pull off a leaf. I imagine the “weed” portion of its name comes from the fact that it grows as readily as any weed in my yard. I find milkweed to be incredibly prolific!

When I pull up unwanted plants, I’ve had success putting the root of the “weed” in a vase of water and once root growth is evident, I transfer it to a pot and give the plant to a friend or a client.

In the early months of winter, I plant milkweed seeds in a plastic gallon milk jug. After drilling a few holes in the bottom, I cut the jug about 3 inches from the bottom about 2/3 of the way around, leaving intact a small section under the jug handle. This allows me to swing the jug open and add soil where I usually plant 5 seeds: 1 in each corner and 1 in the center. I tape the cut jug shut and I leave the top open to permit air circulation and watering.

The jugs are left outdoors throughout the winter. They receive water from natural rainfall or snow and receive the protected stratification (or period of cold) they need to trigger eventual germination when the soil warms in the spring. This strategy has been fairly successful for me but there are other strategies as well! One last note if you are thinking about growing milkweed: try to find a variety that is native to your area. The fate of this beautiful butterfly (recently added to the Endangered Species list) depends on the restoration of their breeding habitat. In the comments section, please share news about monarchs in your yard and of your plans to plant milkweed and please share this article with your social circles. With gratitude -Rachel